Legend and mythmaking are the backbone of the Western genre. As the classic John Ford Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance once emphasized, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” If this sentiment serves as the epigraph to the genre, then the mascot of legend-making would undeniably be one of the stars of Liberty Valance and a countless number of Westerns, John Wayne. Symbolizing the ideal American patriot, Wayne’s films and screen presence are still revered today, but his earnest and simplistic approach to portraying morally complex cowboys and law enforcement figures is pastiche. While his films with Ford and Howard Hawks were often probing and revisionist, Wayne, partially due to his outspoken nationalist political views, feels rooted in fantasy. However, there is one Western of his, The Cowboys, described as one of the most accurate portraits of the Wild West.

John Wayne Aged Into a Father Figure in ‘The Cowboys’

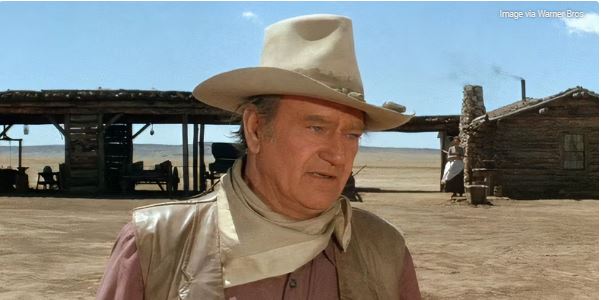

In his late 60s, John Wayne was still a viable movie star. As New Hollywood began to overthrow the old guards in the industry, Wayne remained steady, using his rich iconography in Westerns and war epics like The Green Berets, True Grit, Rio Lobo, and Big Jake. In the context of the Western genre’s vast history, The Cowboys is perhaps the most prominent late-period Wayne picture. In the film, directed by Mark Rydell, future director of On Golden Pond, rancher Wil Andersen (Wayne) is forced to hire local schoolboys to get his cattle herd to market on time. Their journey is hindered by a rough drive full of dangers, notably a gang of rustlers trailing them. Leading cattle herds and military calvaries is a familiar milieu for Wayne, as seen in his classics, including Red River and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. Starring alongside Wayne is Roscoe Lee Browne, Bruce Dern, and Slim Pickens.

Based on a novel by William Dale Jennings, The Cowboys received mixed reviews upon release in 1972. This was the year of The Godfather, Cabaret, and Deliverance, exciting and provocative films by unique visionaries, so something as classic as The Cowboys looked especially outdated. Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film was “flecked with minor dishonesties,” describing it as a parody of Westerns. Canby also noted the broad characterization of Wayne’s character, who acts as a holy father figure to the reckless boys he hires. Under the hands of a visionary director like Ford or Hawks, Wayne’s characters were fleshed out, breaking the rigid noble American hero archetype, but in lesser projects, his limited range as a performer becomes glaringly evident. Roger Ebert was a fan of The Cowboys despite its maudlin ending (featuring a rare death by a Wayne character) that spoils the film’s chances at being something better than a “good-to-fine Western.” Today, The Cowboys is viewed as a last hurrah for Wayne, who gives one of his best performances in this Western swan song.

John Wayne Defined the Western Genre Throughout His Career

In more ways than none, John Wayne embodied the Old West and the Western genre entirely. Across his filmography, the Duke made over 80 Westerns, his most famous work in the genre being envisioned by John Ford and Howard Hawks. With his gravelly voice, imposing stature, and lumbering walk, Wayne was born to play heroic leading men in the new frontier as a herder, sheriff, or soldier. As the young, hot-shot Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, or the seasoned veteran, Wil Andersen, unphased by any danger in The Cowboys, Wayne evoked whatever feeling or psychological complex a Western film called for. Wayne’s indelible iconography was the cherry on top of Ford’s mythic image-making, visualized by awe-inspiring vistas and horizons never framed in the middle of the screen.

Within the same film, such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or Rio Bravo, Wayne could seamlessly shift between steely heroism and sensitive wistfulness. Revisionist history likes to dismiss Wayne’s abilities as an actor, and while his personal life has been the subject of criticism, his wide range of implicit emotions could only be captured by the finest movie stars. Naysayers will argue that he lacked any flair as a performer and was limited in his expressiveness. This perception arises from Wayne’s ability to make his stardom and talent feel effortless, as he could imbue any scene with triumph, pathos, or romance through the simplest gestures. While he never “transformed” as an actor — arguably an overrated concept, Wayne understood the invaluable power of his screen persona and used it to add meta-textual weight to each film. The Cowboys will never be remembered as a totemic work, but the 1972 film keenly underlines the minimalist potency of the Duke’s acting.

The history of the West, and even cinema to a certain extent, can be tracked through John Wayne’s filmography. Before Stagecoach, the breakout film for Wayne and Ford, Westerns were widely marginalized as trivial, cheap entertainment. The classic 1939 film abo

ut a group of disparate travelers, including Wayne’s Ringo Kid, a notorious, wrongfully imprisoned outlaw, symbolized America as the ultimate melting pot. By the 1960s, Westerns gradually became increasingly cynical, with the revisionist Western fully en vogue thanks to the films of Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah. Predating their work was The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Ford’s deconstruction of Western justice, and Wayne’s sobering reflection of his image as the noble vigilante. The film presciently outlined that the cowboy figures of his kind would fall out of fashion, and society would long to valorize upstanding civilians like Jimmy Stewart’s Ransom Stoddard. Between these groundbreaking films, Wayne’s characters reflected the fleeting sense of American optimism amid racial tensions with Native Americans in The Searchers and the loss of folksy innocence in The Quiet Man.

While most of John Wayne’s films from the ‘70s were forgettable, The Cowboys teases how effective he could’ve been in his 60s and 70s with proper guidance, as the 1972 film, along with its accurate portrayal of the West, shows the Duke at his most grounded as a result of his sturdy gravitas.

An Old West Historian Praised the Historical Accuracy of ‘The Cowboys’

It’s fascinating that Canby found The Cowboys hokey and artificial, as one expert claims that the John Wayne movie is one of the most authentic portrayals of the West to ever grace the screen. Michael Grauer, an Old West historian, sat down with Insider to deconstruct legends by rating the authenticity of various Western scenes in movies and television. Grauer praises the verisimilitude of The Cowboys. Rather than his ranch crew being made up of sharp-shooting gunfighters and experienced cattle drivers, Wayne’s Wil Andersen character hires juveniles to help carry the load, which reflects the real experiences of cowboys. “The things they encounter along the way are pretty accurate,” Grauer says. He analyzes many seminal Westerns of classic Hollywood and modern times, such as The Searchers and Django Unchained, but neither captures the essence of the period.

As Michael Grauer outlines in the Insider video, the Western genre has a complicated history regarding historical accuracy. “The greatest myth about the West is that everyone was a gunman —that’s a bunch of nonsense,” Grauer said, referring to the mesmerizing final stand-off in The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, a film he claims “defies credulity.” This crystallizes why Grauer sings The Cowboys’ praises, as it shows a Western lifestyle about blue-collar labor and not glamorized pistol duels. During Western expansion in the latter half of the 19th century, most towns forbade civilians from possessing firearms. While he doesn’t discuss Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, Grauer would presumably admire the film’s portrait of Bill Daggett, Gene Hackman’s sheriff who bans firearms in the town of Big Whiskey, which underlines the power dynamic of the period. On what occurred at the gunfight at O.K. Corral, as depicted in Tombstone, Grauer states that it’s nearly impossible to craft an authentic portrayal, as all documentation of that storied event was misleading to benefit a respective party.

Hollywood’s depiction of Native Americans and other non-white figures in Westerns is a thorny issue on its own. The Searchers is arguably the most influential Western of the 20th century, but Grauer cites that the long-standing conflict between cowboys and Native Americans is a misconception, as the battles shown in The Searchers were a rarity. When they encountered each other, most cowboys or cattle drivers were willing to settle differences via taxing, and Grauer believed the film failed to properly differentiate between Comanche and Navajo tribes culturally. While Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves is viewed with great skepticism due to its white savior complex as a dramatic crux, Grauer finds its treatment of the Lakota Nation to be sympathetic. The Cowboys was groundbreaking in 1972 for casting a black actor, Roscoe Lee Browne, who later became an acclaimed theater actor performing Shakespeare and August Wilson plays, in the part of the chef on the cattle trail.

Speaking of Costner, for all his ambitious spectacle regarding his ongoing Horizon saga that may or may not be completed, he previously made one of the most nuanced and understated Westerns in recent memory in Open Range, a film depicting a cattle drive with similar authenticity to The Cowboys. Grauer praised Costner’s film for its understanding of free grazing, a widespread practice during Western expansion. Cattle drives are inherently more truthful to the Western experience. Some Westerns, such as Howard Hawks’ Red River, belong in the canon of totemic Westerns, but the films of this milieu are less appealing to studios than ones with epic gun fights while riding on horseback.

While it does not have the storied legacy of The Searchers, Stagecoach, or Rio Bravo, The Cowboys is an essential movie in the John Wayne canon. Wayne himself certainly feels that way, as he once described shooting The Cowboys as “the greatest experience” of his life. While he played many paternal figures in the past, the Mark Rydell film signaled a passing of the torch, with the aging Wayne’s Wil Andersen imparting wisdom on to the youth working on the cattle drive. The director once suggested that the torch-passing sentiment drew Wayne to the story. To top it all off, The Cowboys was blessed with an authentic depiction of life on a ranch in the Old West, according to one historian. Wayne was usually a mythical figure, but as he aged into his 60s, he became less sensational and more seasoned.