The online commentary about a Playboy interview unearthed from 1971 shows a lack of education about the western actor, his times and even American history

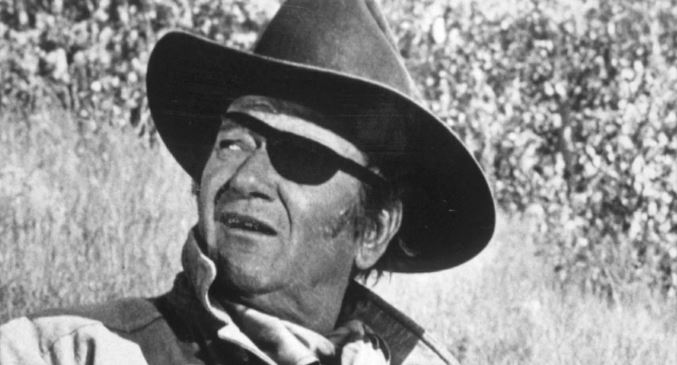

Dusting itself off after the excitement of Liam Neeson’s racist meltdown, the film world has settled on its next talking point, an old interview of John Wayne, recently dug up, in which the actor is revealed to have been racist and homophobic. ¡Escándalo!

In the interview with Playboy magazine from 1971, the actor born Marion Morrison states, among other things “I believe in white supremacy” and calls Midnight Cowboy “a story about two fags”. Shocking stuff from an actor famous for his contribution to the notoriously liberal cowboys and indians genre, who supported Richard Nixon, and directed The Green Berets in support of the US Army during the Vietnam war. Who would have thought? While these views appear shocking now, they aren’t a particular point of astonishment to anybody who knows anything about Wayne, or cinema, or history.

In one sense, revisiting Wayne’s views is important: we should be mindful to revise and decolonise the film canon, and it’s essential to reassess cinema’s heroes in the light of our shifting politics. Many of the films that Wayne made rest on a completely racist ideal, which others and stigmatises non-white cultures, and claims America for white people. A quick trawl through critical writings on Wayne shows that our culture is still not adequately condemnatory of this: as recently as 2011, the critic Roger Ebert could still write of Stagecoach, that: “the film’s attitudes toward Native Americans are unenlightened. The Apaches are seen simply as murderous savages; there is no suggestion the white men have invaded their land … Ford was not a racist, nor was Wayne, but they made films that were sadly unenlightened.” Ebert’s euphemism here is painfully insufficient.

There exists a want of nuance in understanding politics in the golden age of Hollywood

On the other hand, it’s possible to feel a certain weariness about a new right-on mindset finding fault with, of all people, John Wayne. Who next, Charlton Heston? Ronald Reagan? Pity the modern film buff who happens, during their internet travels, upon Frank Sinatra’s ill-advised links to organised crime! Seeing a brouhaha erupt over these comments shows that there exists in our discourse a certain incuriosity about the past, a lack of education on movie history, and a want of nuance in understanding politics in the golden age of Hollywood.

John Wayne is wholly synonymous with movie rightwingery, for his films and his extracurricular activities. Not for nothing did he preside for four years, between 1949 and 1953, over the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, which sought to uphold “the American way of life” in films, and protect cinema from “communists and fascists”. This is where a little bit of education comes in handy, because it helps ground Wayne’s views in a cold war combat between “American” values and the supposed evils of communism: the same tussle which saw actors, writers and directors, such as Sam Wanamaker and Dalton Trumbo blacklisted for “un-American activities”. Members of Wayne’s Alliance included Walt Disney, Ronald Reagan and Ginger Rogers, and many of them testified against other Hollywood creatives.

Amusingly, there are parallels with modern actor Kelsey Grammer, who earlier this week was called out online for his pro-Brexit, pro-Trump views. Again, Grammer has been on the record for some time as a Republican. Again, the actor was a member of a Hollywood organisation created for the advancement of rightwing values in the arts: in this case, the embarrassing Friends of Abe, founded by the actor Gary Sinise in 2004, which has met with Republican speakers including Rick Santorum and Glenn Beck. Disappointment with Grammer appears to stem from the fact that, erm, people enjoy Frasier. Once more, a modicum of political nous is all that is required: understanding how retrograde, conservative views proliferate among very rich white people shouldn’t be this much of a stretch.

The farrago over Wayne shows that our response to past and ongoing infractions – such as Neeson’s failure to realise the racism of his comments during the aforementioned coshgate – must be sophisticated. Tackling patriarchal white supremacism and the ways it is reflected in cinema’s deathless obsession with violent films about revenge, retribution and vigilantism, will perhaps not be as enjoyable as pointing at Wayne and laughing, but it’s the task we have ahead of us.