Quentin Tarantino was, for a time, set to cement his legacy as one of the most influential filmmakers of modern cinema with the release of his long-anticipated tenth and final film, The Movie Critic. While the director has now put the idea for that picture to bed, he has still kept his eyes firmly on retiring with a bang.

Over a career spanning three decades, Tarantino has absorbed the lessons of Hollywood’s finest, carefully curating his own approach to storytelling, style, and—most notably—his exit strategy. Unlike many of his heroes who continued directing past their prime, Tarantino has long maintained that he wants to bow out before his work starts to decline. And, rather unusually, a terrible John Wayne western played a crucial role in solidifying that decision.

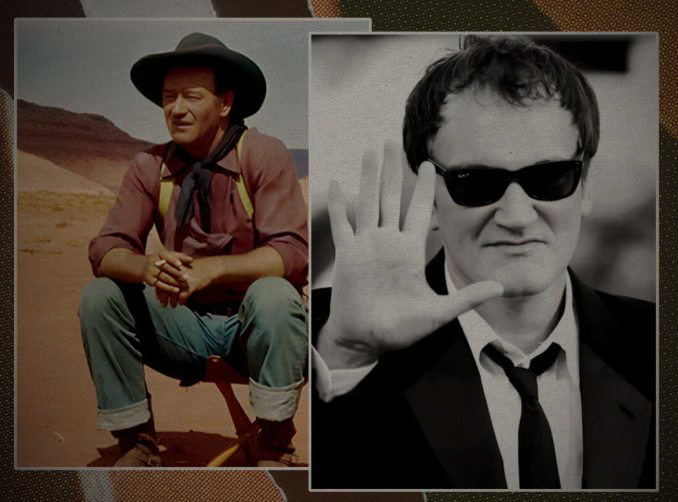

The film in question is Rio Lobo, released in 1970 and directed by the legendary Howard Hawks, a filmmaker Tarantino has openly admired. Starring John Wayne, Rio Lobo was the third iteration of Hawks’ familiar “sheriff against the outlaws” concept, following Rio Bravo (1959) and El Dorado (1966). While both of those films found their place among western classics, Rio Lobo failed to capture the same magic. Despite Hawks’ esteemed legacy—marked by groundbreaking films like Scarface (1932), The Big Sleep (1946), and Red River (1948)—his final feature was a critical and commercial disappointment. Tarantino took it as a cautionary tale.

A lifelong devotee of Hawks, Tarantino has often cited Rio Bravo as one of his favourite films. His admiration runs so deep that he famously uses it as a test for romantic compatibility. If a date doesn’t enjoy Rio Bravo, the relationship is unlikely to go far. However, when it comes to Rio Lobo, Tarantino’s feelings are far less affectionate. To him, it epitomises what happens when a great director overstays his welcome.

A lacklustre retread of familiar themes, Rio Lobo was criticised for its uninspired storytelling and weak performances. Wayne, despite his towering reputation, was already showing signs of age and repetition. Hawks, who had once revolutionised Hollywood with his sharp dialogue and effortless cool, delivered a film that felt tired and out of step with the times. The lack of innovation and the diminishing returns of revisiting the same story struck a chord with Tarantino. He didn’t just dislike Rio Lobo—he saw it as a warning.

Speaking at a Q&A hosted by American Cinematheque in 2010, following a double screening of Pulp Fiction and Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino laid out his philosophy on quitting while ahead. “As far as an artist is concerned in this business, it’s about the filmography. That’s what it’s about. It’s about every one being of a piece. And that’s why I want to get out, at a certain part in the game. I want to live or die by that filmography.”

Tarantino has repeatedly expressed his belief that the coolest, most innovative filmmakers often don’t know when to call it quits. “The most cutting-edge artist, the coolest guys, the hippest dudes, they’re the ones that stay at the party too long. They’re the ones that make those last two or three movies that are completely out of touch and do not realise the world has turned on them. And they have no idea how corny they are.” His goal? To avoid that fate at all costs.

He pointed to Rio Lobo as a prime example of an icon losing touch. But it wasn’t just Hawks—Tarantino also referenced another western legend, John Ford, whose final film, Cheyenne Autumn (1964), lacked the bite and brilliance of his earlier works. And, in the same breath, he mentioned Billy Wilder’s Buddy Buddy (1981) and Fedora (1978) as further cautionary examples of directors who overstayed their welcome.

Tarantino doesn’t want to make Rio Lobo. He doesn’t want to make Cheyenne Autumn. He wants his final film to be as fresh and exhilarating as his debut. Whether The Movie Critic lives up to that standard remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: Tarantino’s exit is as meticulously planned as the movies that made him a legend.