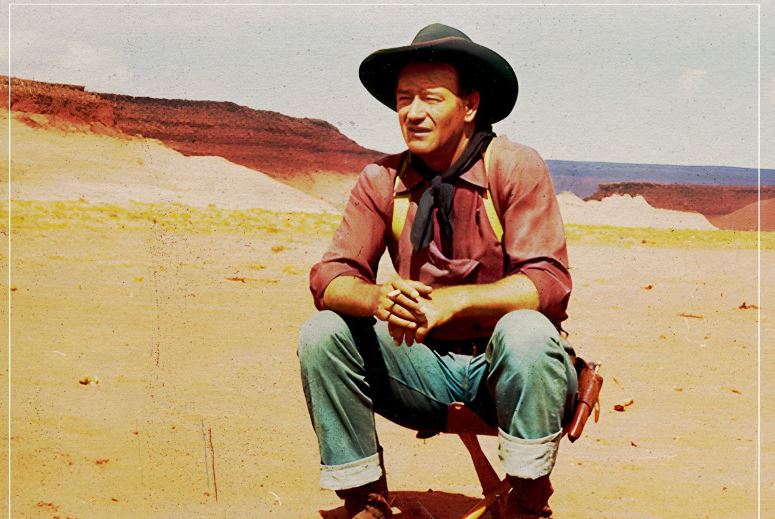

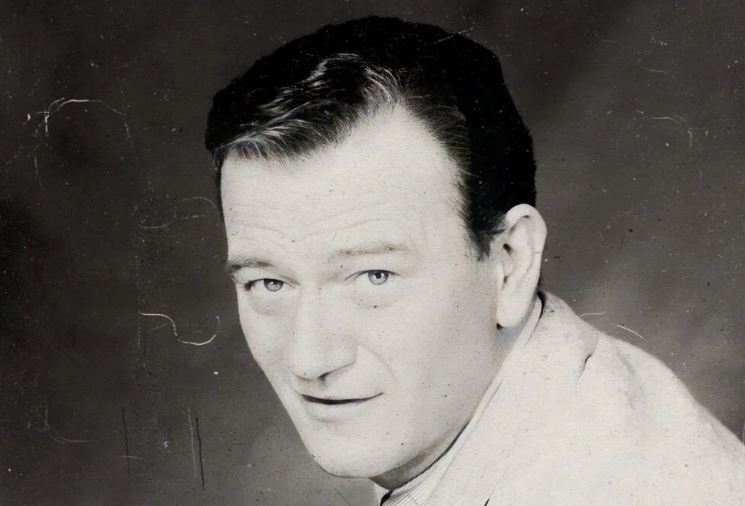

Stardom is regularly a secondary concern for actors who place a desire to test themselves as performers at the forefront of their thinking, but John Wayne didn’t want to be anybody or anything other than John Wayne.

In fairness, it worked wonders for the star when he became a towering figure in Hollywood history, but it was nonetheless limiting in its own way. For one thing, he had a habit of turning down parts that didn’t fit the rigid mythology he’d crafted around himself, and the longer his career went on, the more it felt like he’d been shoehorned into a box of his own making.

Because audiences had spent so long been accustomed to seeing ‘The Duke’ rinse and repeat the stoic, determined, and gun-toting protagonist over such a lengthy period of time, the person and the personality gradually became one. There was no longer any difference between the man born Marion Morrison and the stage name he adopted, which came with its own set of issues.

Wayne may have claimed that he didn’t care what the critics thought about his movies because his number one priority was to entertain audiences, which by extension increased his value, drawing power, earning potential, and bank balance. However, he repeatedly felt he was being overlooked by the Academy.

‘The Duke’ thought he deserved to be nominated at the very least for John Ford’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, but he only ever made the Oscars shortlist three times. One of them was for ‘Best Picture’ when he produced his self-directed historical epic The Alamo, so the legend only ever earned two acting nods.

They came 20 years apart, too, with his maiden nomination for war drama Sands of Iwo Jima being followed a full two decades down the line by True Grit, which finally nabbed him the big one. The part of Rooster Cogburn wasn’t a million miles outside of Wayne’s wheelhouse, but he fully believed he got exactly what his performance merited.

Reuniting with director Henry Hathaway for the fifth time after Legend of the Lost, North to Alaska, Circus World, and The Sons of Katie Elder, even before it was released, the actor knew that the pressure was on him to deliver. Fortunately, he was so confident in the character he made a rather lofty claim.

“This picture’s got to make a bundle,” he admitted to Roger Ebert of True Grit‘s prospects. “And for a change I have a good part, I’d say this is my first good part in 20 years.” It’s right there in the history books that it won him an Oscar at long last, but was Cogburn really the best thing to have come Wayne’s way for that period of time?

In terms of accolades, it is, but that hardly tells the full story. It was The Duke who made his persona such an intrinsic and unwavering part of his decision-making process, and yet here was lamenting how “everybody else in the picture gets to have funny little scenes, clever lines, but I’m the hero, so I stand there.”

Not to piss on the big man’s chips, but it is possible to do both. Heroes don’t have to be one-note, one-dimensional vessels used to dispatch bad guys and save the day, something Wayne himself had showcased repeatedly in some of his greatest-ever pictures in that 20-year period between Sands of Iwo Jima and True Grit.

Between those two points, he anchored Rio Grande, The Quiet Man, Rio Bravo, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, all of which saw him in sparkling form. Admittedly, there wasn’t a great deal more to his work than going through the greatest hits and displaying the megawatt charisma that made him a household name in the first place, but there’s one hefty elephant in the room that can’t go unmentioned.

13 years prior to True Grit, Wayne partnered with Ford for a little film called The Searchers, which is regularly touted as the magnum opus of both men’s careers. Ethan Edwards, as a character, is a fascinating protagonist, a remorseless and ruthless bigoted racist who hates everything around him while maintaining a moral compass so rigid he’ll do anything to protect the people he loves.

Did Wayne deserve an Oscar for True Grit? Probably. Was it the most complex and well-rounded part he’d played in 20 years? Not when The Searchers fits into that timeline, it isn’t. At the very least, it was disparaging to several films, but ignoring his phenomenal contributions to a morally grey antihero in the single greatest western in Hollywood history makes for a fairly egregious oversight.