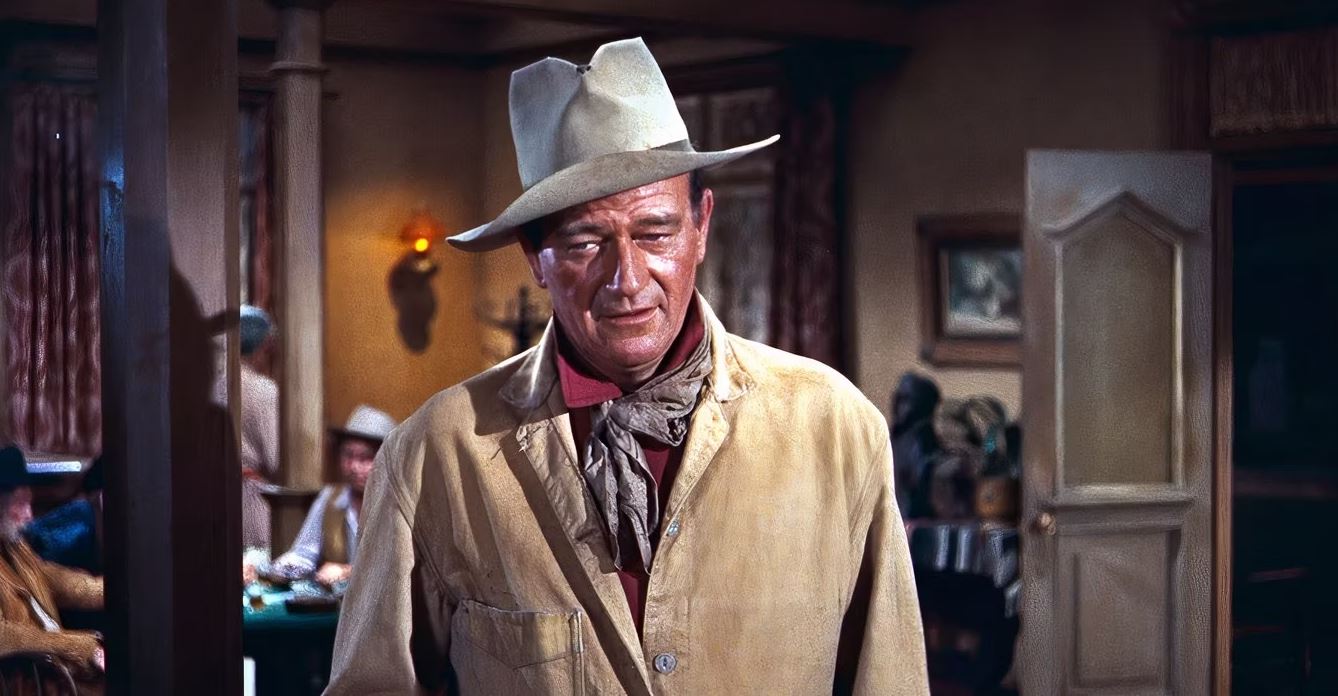

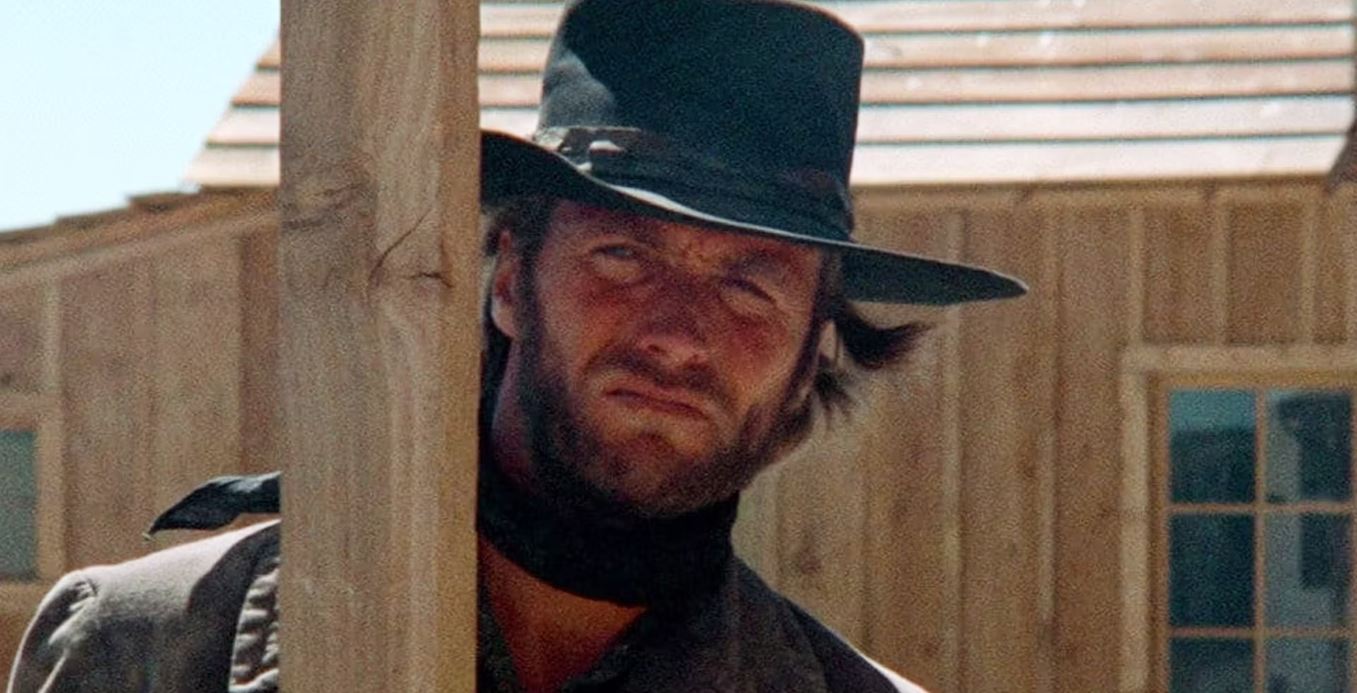

Throughout cinematic history, two actors stand heads and tails above everyone else regarding Westerns. Those two men are John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. Throughout their heralded careers, the two men never worked together, even though they were once offered the opportunity to do so. Instead, politics, ego, and machismo got in the way.

The truth is that Clint Eastwood and John Wayne did not get along. The reasons for this are varied and complicated. Neither man was a fan of the other, and John Wayne certainly felt a certain way when he realized that Clint Eastwood was slowly replacing him as America’s favorite cowboy. As Eastwood’s star continued to rise during the reinvention of the Western in the 1960s, Wayne grew increasingly bitter, outright condemning the genre’s evolution and not only refused to acknowledge its newfound popularity but outright terminated the one chance both men had to work together.

Two Cowboys Riding In Opposite Directions

One a Hero, the Other an Anti-Hero

When Clint Eastwood emerged as one of America’s most promising new movie stars in the 1960s, John Wayne’s glory days were already fading in the rearview mirror. Outside of his Academy Award win for True Grit in 1970, the man known as the Duke could only sit and watch as the type of roles he used to book went to actors younger than him. Actors like Clint Eastwood.

After debuting on the hit television series Rawhide, Clint Eastwood became one of Hollywood’s most bankable actors thanks to his star-making turn in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars. That, in turn, led to the completion of the Dollars trilogy, which resulted in Eastwood’s being hired for a role that John Wayne had infamously turned down, “Dirty” Harry Callahan.

Thanks to the incredible success of the Dirty Harry franchise across five feature films, Eastwood became a new type of cultural icon — one who personified more of a modern-day antihero than the classical men of honor that John Wayne used to portray. As Eastwood’s career progressed, he perfected something John Wayne never entirely succeeded at: directing. After helming (and starring) in movies like High Plains Drifter and The Outlaw Josey Wales, the disconnect between these two men increased as Wayne became increasingly frustrated with how Eastwood represented heroism on-screen.

John Wayne approached his many Westerns as an opportunity to uphold and promote his staunch conservative beliefs about America. From his perspective, Clint Eastwood undid all that hard work by painting in shades of gray rather than the stark contrast of black and white or good versus evil. In short, John Wayne perceived his battle against Clint Eastwood as a changing of the guard, and he fought bitterly hard to maintain what he perceived as the purity of the Old West.

Why Did John Wayne Hate Clint Eastwood?

A Changing of the Guard is Never Easy

John Wayne and director John Ford defined the 20th-century Western during their incredible run together. Their films often featured charming, starry-eyed characters who were probably a bit out of touch with the actual reality of that rough-and-tumble historical period. Wayne wanted to idolize the West. Clint Eastwood’s Westerns, on the other hand, had questions, most of which entailed ambiguous morality and the questioning of American Exceptionalism. Even when Eastwood’s films didn’t address these themes directly, the undercurrent remained.

John Wayne was diametrically opposed to such progressiveness. The more Eastwood’s star eclipsed his own, the more these ideas grew and the angrier Wayne got. As the Western genre found itself redefined by a series of revisionists and continued to capture the heart of filmgoers, it was more apparent than ever that a new generation of Americans preferred a grittier, darker, and unforgiving depiction of the Old West, which directly contradicted Wayne’s romantic idealization of the genre.

High Plains Drifter was the inflection point of Clint Eastwood and John Wayne’s feud. The film follows a mysterious drifter and gun-fighter played by Eastwood, who finds himself hired by a local town to defend its community against three particularly violent outlaws. The thing is, Eastwood’s “hero” is just as dark and vicious (if not more so) than the outlaws. The specific kind of justice Eastwood’s Stranger delivers to the town is teased as being satanic, further blurring the lines between good and evil by inserting religion into the whole mix.

John Wayne, a traditionalist in nature, had a close relationship with God and even converted to Catholicism shortly before his death. In other words, he deeply resented and was disgusted by Eastwood’s character in High Plains Drifter and even went so far as to write a scathing letter, which he sent to Eastwood, stating, “[High Plains Drifter] wasn’t really about the people who pioneered the West.”

In Eastwood’s defense, he wasn’t trying to make a film documenting what people were like in the Old West with High Plains Drifter; instead,

he was looking to create a fable. After receiving the letter for Wayne in the mail, Eastwood realized something else as well. Specifically, two generations of Americans were now arguing over what the West was truly like, and neither side understood the other. But there’s something even more shocking to learn about that letter John Wayne sent to Clint Eastwood. It was written in response to Eastwood asking Wayne to star in a picture with him.

Did Clint Eastwood and John Wayne Ever Come Close to Working Together?

It Came Closer Than You Think

At some point in the early 70s, acclaimed B-movie director Larry Cohen had himself something of a pipe dream. That dream was to get Clint Eastwood and John Wayne together for one film, a Western Cohen was writing titled The Hostiles. To this day, not much is known about the script, but it was said to have focused on a young gambler (to be played by Eastwood) who wins half the estate of an older man (to be portrayed by John Wayne).

Eastwood was impressed enough by the script to option it from Cohen and agreed to try to convince John Wayne to board the project. After sending Wayne the script, the older actor saw the film as nothing more than a continuation of the spaghetti Western style and refused to star in it. So, Eastwood tried again, this time with a revised script. Still no luck. That’s when Wayne sent Eastwood a letter clarifying his refusal while badmouthing High Plains Drifter.

Even after all that, Eastwood sent Wayne the script one last time. When Wayne’s son, Mike, handed it to him while the two men were out sailing, the former superstar gruffly said, “This piece of sh*t again,” and threw the script into the ocean. Eastwood never reached out again, and the closest the two men ever came to working together was when John Wayne teamed up with Eastwood’s frequent director, Don Siegel, for his final screen performance in The Shootist. One day, Eastwood visited the set, and Wayne only agreed to meet him after discovering that Eastwood’s political views were as staunchly Republican as his own.

What Does the Feud Between Wayne and Eastwood Represent?

The Last Generation Will Always Struggle to Understand the Next

John Wayne passed away in 1979. Since his passing, Eastwood has taken on the mantle of America’s favorite cowboy without reservation and provided one of the genre’s defining moments with his Academy Award-winning film Unforgiven. Following that monumental release, the Western genre began to sag in popularity, at least in movies. While the genre has thrived on television, cinematic masterpieces are few and far between, and no singular actor has captured an entire generation’s attention as a quintessential gunslinger.

Considering that outcome, maybe there was something to what John Wayne was saying. Perhaps Westerns could truly only thrive in movie theaters by offering audiences escapist thrills and action, not questions about morality. True, Wayne’s politics blinded him from the many redeeming qualities of spaghetti Westerns and their ilk. Having made so many throughout his storied career, perhaps Wayne had tapped into a zeitgeist that no one else could adequately perceive.

That said, Clint Eastwood’s career is nothing short of remarkable. He didn’t restrain himself to only the Western genre, as Wayne did. Instead, he became the natural evolution of Wayne and his filmography by questioning and re-examining the type of violence that the United States of America was built upon.