As a factory of escapist entertainment, Hollywood understandably didn’t want to touch the Vietnam War in the late 1960s. Every day, Americans turned on their televisions to watch extensive war coverage and ground-level combat footage. They flip over to the next channel to find coverage of hostile, sometimes violent, protests at home. It was a dark time in American history, so movie theaters became a safe haven, where Hollywood provided them with glossy musicals and historical epics. In their minds, audiences needed to be reminded of America’s halcyon days post-World War II. This explains why one of the rare Vietnam movies of the period, The Green Berets, is coded like a WWII man-on-a-mission epic and starred an overage John Wayne substantiating the myths and lies fed to the people about the war by the American government.

John Wayne Received Support From the U.S. Military When Developing ‘The Green Berets’

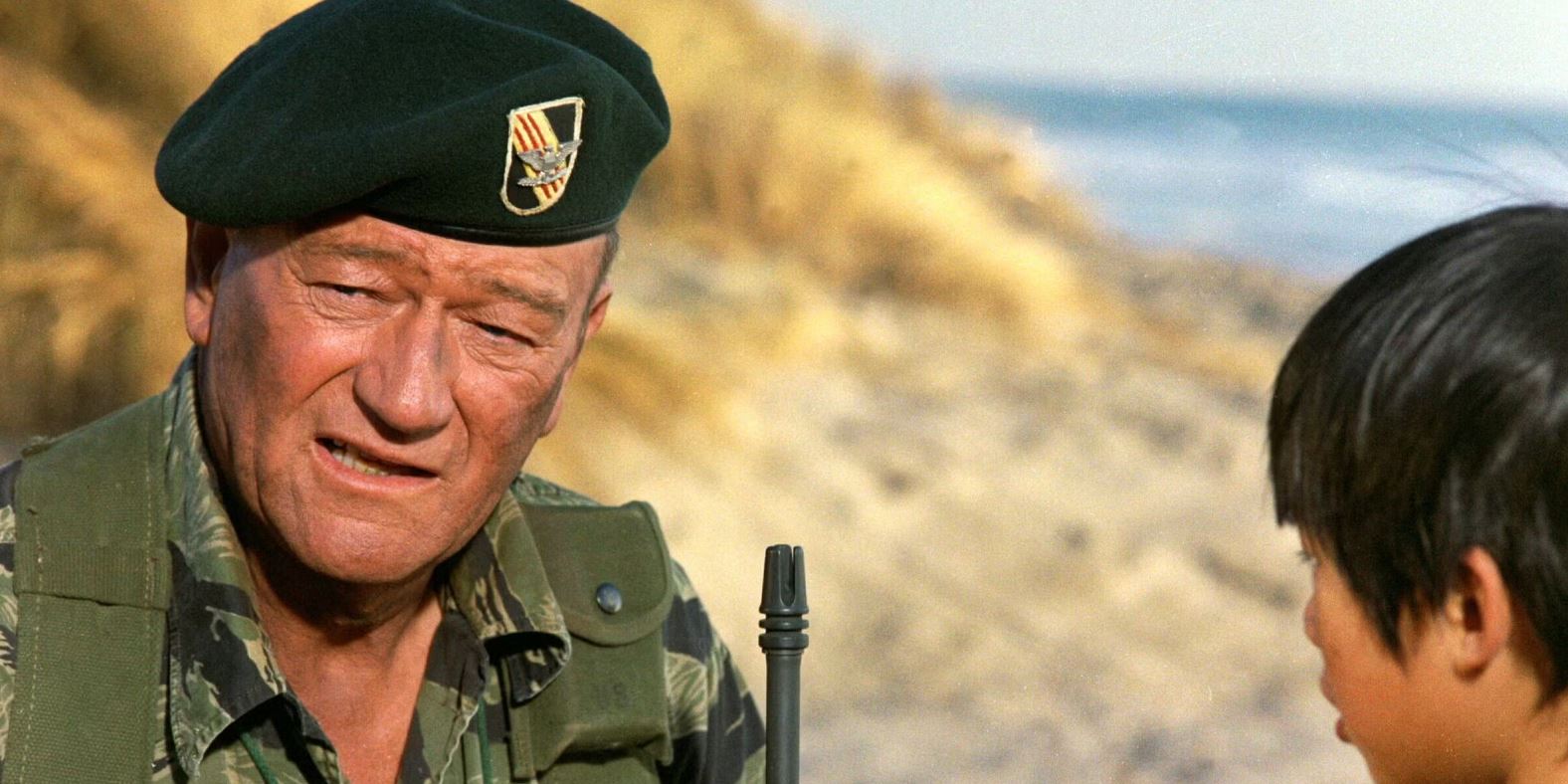

In the late 1960s, an aging John Wayne was not at his artistic peak, but he ascended to the apex of his stardom, evolving from “just a movie star” to an American icon. While directors like John Ford and Howard Hawks actively deconstructed and reexamined his screen image, late-period Wayne films were inclined to glorify him as a mighty soldier or sheriff. With the ongoing Vietnam War looming large over America, Wayne was unafraid to express his anti-communist and nationalist rhetoric. Nowhere did he have a bigger platform than with his 1968 war film, The Green Berets, which he directed with Ray Kellogg. The film, loosely based on the novel by Robin Moore, follows Colonel Mike Kirby (Wayne), who leads two crack commando teams into South Vietnam to build and control a camp being captured by enemy forces and kidnap a North Vietnamese general while aiding the South Vietnamese army.

America’s involvement in the war was exacerbated in 1968, the year of the Tet Offensive. The year not only saw carnage in the jungles of Vietnam but also in the streets of America.

Between the infamous Chicago Seven riots at the Democratic National Convention and the draft sending the youth of the nation into a war without a cause, American spirits were in the dumps, but John Wayne was going to lift us up. Struggling to receive funds from studios, Wayne petitioned for support from the U.S. Government by writing a letter to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Seeing the film’s potential to paint a sympathetic portrait of the war, they agreed to cooperate with the production. The Duke’s son, Michael Wayne, was the film’s diplomat, traveling to Washington to receive Pentagon consultation on the script. The government’s backing of the film is evident in The Green Beret’s authenticity as a combat movie, as the Department of Defense provided the production with all the necessary military equipment and machinery.

‘The Green Berets’ Gets the Vietnam War All Wrong

John Wayne stepping up and receiving funds and support for a film about a subject no studio wanted to touch would’ve been an impressive display of creative independence if The Green Berets had anything worthwhile to say about the ongoing international conflict. Upon release, critics immediately sniffed out the agenda Wayne was trying to push. In a scathing zero-star review, Roger Ebert wrote that the film was “heavy-handed” and “remarkably old-fashioned,” one that streamlined the backdrop of a complex war to tell a story of “cowboys and Indians.” A New York Times review described the film’s fantastical wartime myths as “so unspeakable, so stupid, so rotten and false in every detail.” Even when disregarding Wayne’s political motivations, attempting to reflect on the Vietnam War while the conflict is at its peak is an ill-fated strategy.

The Green Berets, with its toothless depiction of the war and broad vilification of the enemy, serves as the blueprint for how not to make a Vietnam film. The film’s legacy is a dichotomy to future Vietnam classics, such as Apocalypse Now, Platoon, and Full Metal Jacket. Unsurprisingly, the Department of Defense denied Francis Ford Coppola’s request for military backing for Apocalypse Now, which presents the war as an existential nightmare, debunking the myths carried out by the nation. With Platoon, Oliver Stone integrated his experience as a Vietnam veteran to envision a documentary-like facsimile of the war coverage shown on TV. By the mid-1980s, Vietnam became a reliable genre in Hollywood once enough time passed and filmmakers with skeptical eyes emerged. The Green Berets, released during a period when America still had no idea who they were fighting or what they were fighting for, couldn’t say anything profound or cutting about the war, especially since its star and director, John Wayne, merely conceived a propaganda film.

John Wayne Has a History of Playing Soldiers in Movies

More so than playing cowboys and sheriffs of the Old West, an archetype the legendary movie star defined across multiple decades, John Wayne specialized in playing war soldiers and generals on the battlefront. It seemed logical that Wayne, the American ideal for a brave, masculine hero, would be inserted on a combat field as a cavalry leader or general in the jungles of Vietnam. Amid all the chaos and destruction of war, his prodigious stature and complex will always be the main draw for the camera, making him a desired object for all directors to capture on screen. Prior to winning an Oscar for his late-career turn as Rooster Cogburn in True Grit, the Duke’s lone acting nomination came from The Sands of Iwo Jima, an Allan Dwan film about a cold and hard-nosed sergeant who earns the respect of his officers upon hitting the Pacific beaches. The film is an earnest and jingoistic portrait of the U.S. military that has fallen out of fashion with contemporary viewers, but it distills Wayne’s public persona to a tee — even if it isn’t exactly one of his finest performances.

Throughout his career, culminating in The Green Berets disguised as a Vietnam movie while actually glorifying American exceptionalism, Wayne loved to remind audiences of the triumphant victory America and the Allied nations experienced during World War II. One of his most famous returns to WWII late in his career was The Longest Day. To its credit, this war film about the fateful D-Day landing in Normandy in 1944 was shot like a documentary in the vein of Saving Private Ryan, and it also tracked the monumental battle from opposing perspectives, adding to the operatic and world-altering stakes of this day. One of Wayne’s most reflective and poignant war films naturally arose from the guidance of his best collaborator, John Ford, whose WWII-set movie, They Were Expendable, underscores the fatalism of fighting for a noble cause. For the most part, however, most of his war films, like The Fighting Seabees in 1944, were outwardly patriotic and straightforward as pieces of entertainment.

The event that lingered over John Wayne’s career and personal life, perhaps more than any, was his decision not to enlist in the armed forces during World War II. While many of his past and future collaborators, such as Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, and John Ford, all fought to protect Western civilization, Wayne wanted to increase his cachet as a star. Years later, his vast array of patriotic war movies, as well as his outspoken staunch conservative political views, arguably signaled an effort to overcompensate for his lack of service during one of the defining moments in American history. The Green Berets is the kind of sanitized depiction of war that someone who didn’t serve idealizes from afar.