John Wayne and William Holden were paid a then unheard-of $775,000 each to star in The Horse Soldiers, but the movie was a box office bomb and plagued by tragedy

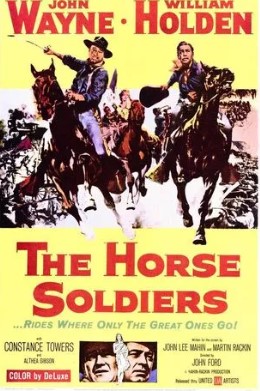

In 1959, John Wayne and his frequent collaborator, fellow Hollywood conservative John Ford, worked together on the filmmaker’s only full American Civil War movie. Wayne and his co-star in The Horse Soldiers, William Holden, negotiated a staggering $775,000 (nearly $8 million today) each, plus 20 per cent of the total profits.

This was an unprecedented amount at the time, but there were no profits to share as the film was a box office flop with a “lacklustre” response from critics and audiences. The failure was even more bitter given the extreme difficulty of making the film.

Not only were Holden and Ford constantly at odds, but there were also cost overruns, serious injuries, and even a tragic death. All this while the director, who was known for his heavy drinking, had been ordered by his doctor to quit alcohol or risk dying from its side effects.

This made the notoriously grumpy and uncompromising filmmaker even more unbearable for Wayne, who was at his wit’s end. Ford, known for baiting his cast to elicit better performances (including regularly insulting Wayne for not serving during World War II), was even tougher than usual.

Despite Wayne not having to quit drinking, Ford insisted that Duke do the same on The Horse Soldiers set. In the end, the star pleaded with producer Martin Rackin to give him a break from the director he referred to as Pappy, reports the Express.

The producer, in a blatant lie, convinced Ford that Wayne and Holden’s teeth were appearing yellow on film, necessitating a whitening procedure in New Orleans. This led to a wild night out in Crescent City for the trio, which ended with an irate Ford discovering through his informants the number of bars they had frequented.

During the shoot, Wayne was grappling with a personal crisis involving his wife Pilar. Pilar had developed a barbiturate addiction, but Wayne was reluctant to admit her to a private sanitarium, believing he could help her recover while on location in Louisiana.

However, during filming, his wife began experiencing hallucinations and even attempted suicide by slashing her wrists. At this juncture, Duke realized he needed to hospitalize her back in Encino, California.

Remarkably, this incident was kept out of the press. Meanwhile, back on The Horse Soldiers set, three actors, including Ford’s son Patrick, sustained broken legs.

But the ultimate tragedy occurred during the filming of the movie’s climactic battle scene.

Veteran stuntman Fred Kennedy tragically lost his life while performing a horse fall for the movie, breaking his neck in the process. Biographer Joseph Malham revealed: “Ford was completely devastated [as he] felt a deep responsibility for the lives of the men who served under him.”

Following this heartbreaking incident, filming was immediately halted and relocated to Hollywood.

At this point, Ford had completely lost interest in shooting the scripted ending featuring Wayne’s character Colonel John Marlowe and his forces arriving in Baton Rouge. Ultimately, he chose to conclude The Horse Soldiers with the lead’s farewell to Constance Towers’ Hannah Hunter before crossing and blowing up a bridge to halt the Confederate advance.

Despite Ford’s tough exterior, he was progressive for his time, advocating for Black actors in the segregated South where they were filming the movie. Tennis champion Althea Gibson was cast as Lukey in an effort to draw African-American viewers to The Horse Soldiers.

However, her dialogue was written in an offensive and stereotypical “Negro” dialect. She stood her ground, telling the director she wouldn’t deliver the lines as they were written.

Surprisingly, despite Ford’s usual inflexibility with actor demands, he agreed, and the script was altered. Furthermore, Ford ensured that the Black extras on location in Louisiana and Mississippi received the same pay as their White counterparts, a move that angered members of the segregated states.